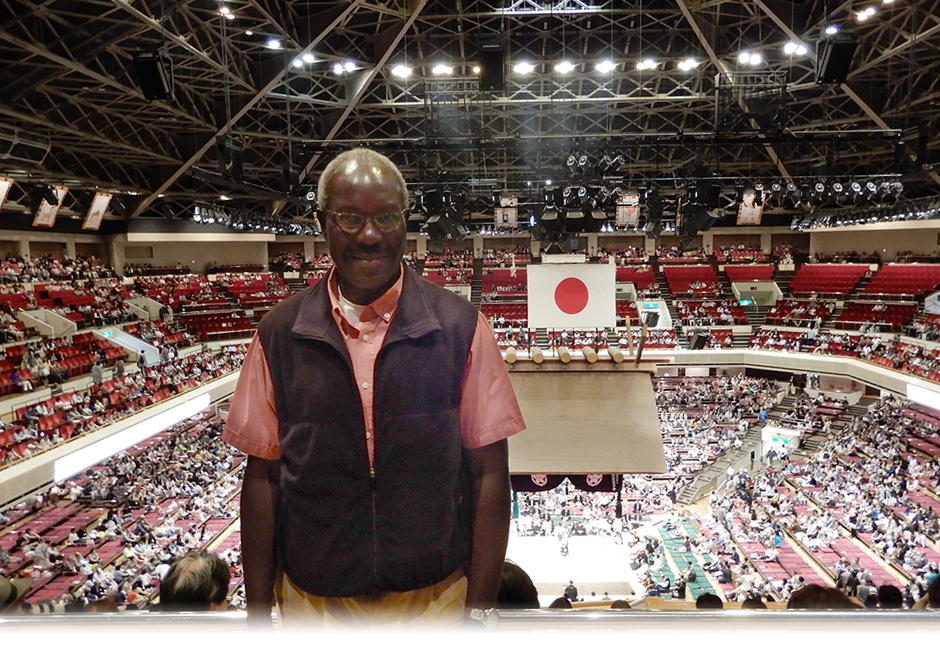

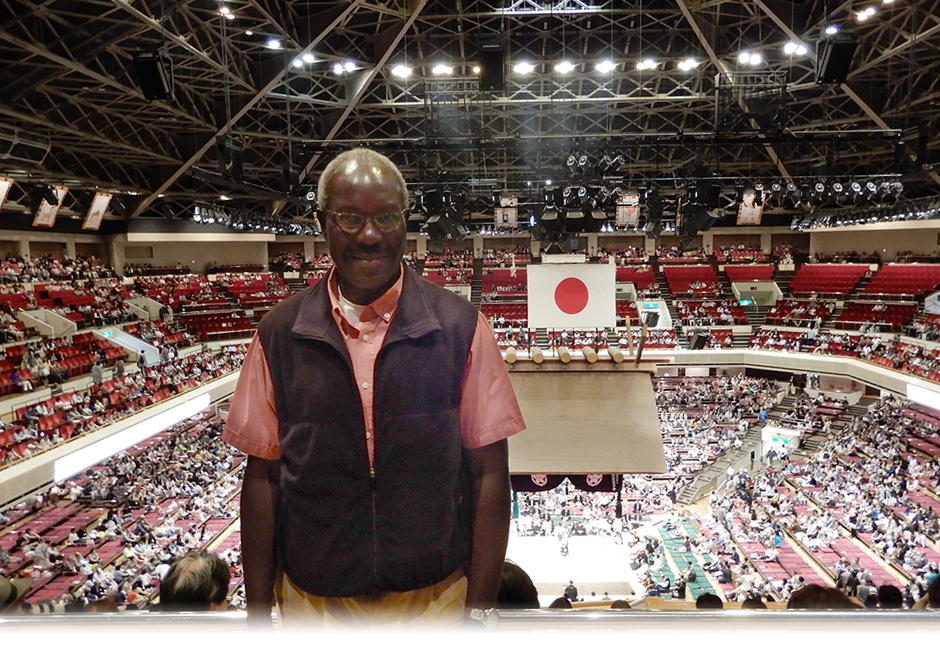

At Kokugikan Stadium for May Sumo Tournament

My Fulbright Story

At Kokugikan Stadium for May Sumo Tournament

“Fulbright is responsible for what I became,” says Prof. Samuel Imbo.

Indeed, his choice of graduate school and eventually where he would put down permanent roots and raise a family is tied to the advice of a Fulbright Fellowship recipient like himself. When he was an undergraduate student in Kenya in the 1980s, a professor told him about the great experience he was having as a Fulbrighter in the U.S.

“So, he asked me to apply to the university that he ended up at, which was Purdue University. That was the only school I applied to, and I got in,” he says. He later received a Ph.D. from Purdue in political philosophy and stayed in the U.S. to teach.

Decades later, Prof. Imbo was the one on a Fulbright.

After earlier summers teaching in Malaysia sparked an interest in learning more about the rest of Asia, especially Japan, he chose Tokyo for his fellowship last year. For a semester at University of Tokyo and Japan Women’s University, he lectured on U.S. history and about U.S. popular culture, emphasizing the contributions of African-Americans.

While he says U.S. and Japanese students have the same familiarity with technology, classroom discussion between students and professors is very different in the two countries.

“It took me a while to register that you are not going to get a back and forth discussion on any topic of the day, so I had to adjust my own teaching to be much more reliant on prepared notes and lectures,” he says. “Arguing ideas and going back and forth may be appealing to Americans. But it may not be as appealing to people in other parts of the world.”

Through his interactions with students — and even more so with colleagues in Japan, he came to understand how people overseas follow events in the U.S. and want to understand them because they are directly affected.

“Now I think about how the issues we are talking about in the United States apply or relate to Japan — or Asia much more generally. Whereas, I would not have been thinking about these things before. Now I do. How do these things play out in another place,” he says.

Prof. Imbo, who is back at Hamline University in St. Paul, Minnesota, says the fellowship also enabled him to expand his relationships beyond the campus.

“I met people — not academics — who came to lectures at universities. I actually struck up conversations with them, and we keep in touch still,” he says. “The Fulbright network has made possible connections that I could not have had otherwise.”

On the days he wasn’t teaching, in addition to visiting parks and shrines, he would take several-hour long walks in Tokyo, without a set destination. “I would have a map but would not consult it. I would just take interesting directions and walk in those directions, and I discovered places I would not have discovered in any other way,” he says. “One of the things I did was get lost a lot.”

Still, through the intervening decades, Fulbright found him — again.

I applied to the Fulbright Program because the timing was perfect professionally and personally. My institution granted me a sabbatical; I could easily re-arrange family commitments; and I wanted to experience Japan through an organization with the long-standing reputation of the Fulbright Program.